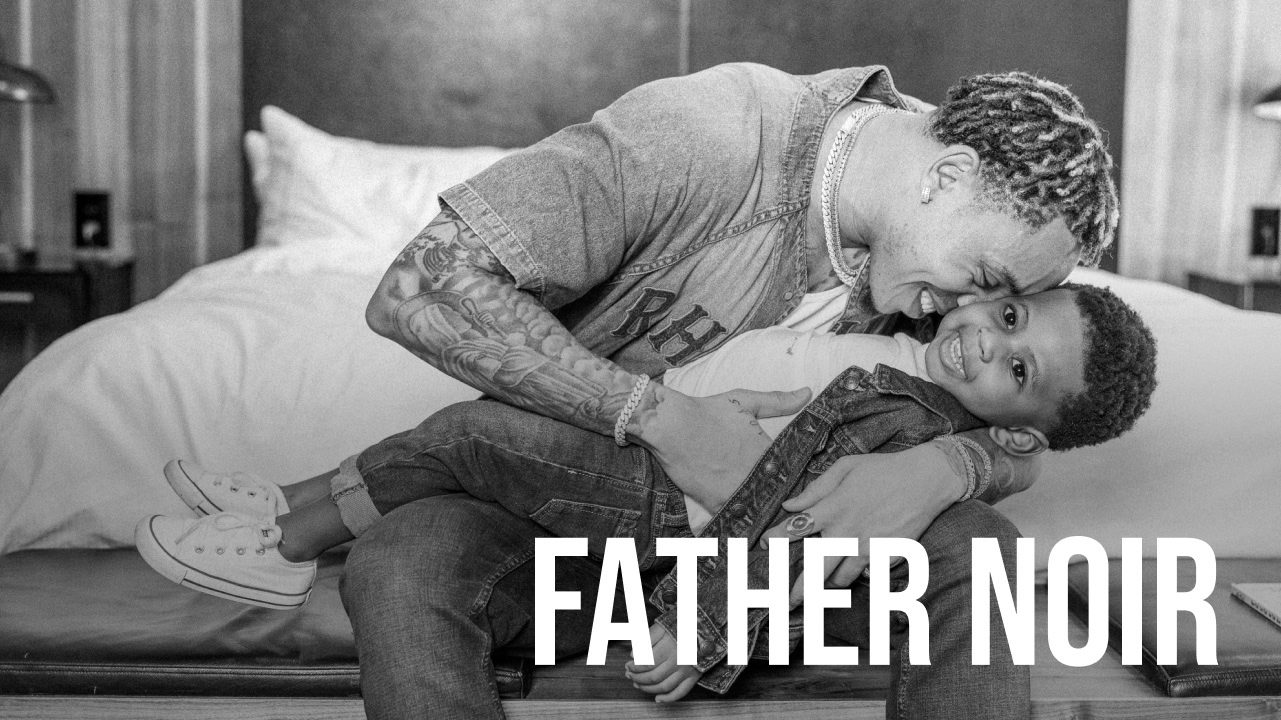

Melanie White Photography

Is great fathering really about allowing my children to take the lead on how they should be parented?

Growing up my father would always use the phrase, “That’s not how I’m wired.” In many situations, that found him like a fish out of water. He would say to me that I was wired differently than he was—which I have come to believe to be true. I am the third of eight children born to Eugene and Lena Burrell in Washington, DC. My mother is creative, outgoing, loves people and deftly managed our household of 10. Resources – financial and otherwise – were limited; being pragmatic, firm, and realistic ruled the day. My father is a stoic man of faith – introverted and strong. He spends a lot of time deep in thought and is very careful with the words he speaks. He is brilliant. He reads avidly and is wholly disinterested in others’ opinion of him. My father was measured in all his ways, including in the display of emotion. This measured approach was beneficial for the world in which he grew up – inner-city Washington, DC – in the 1950s and 1960s.

I am both my father and my mother’s child. I am cerebral like my father and creative like my mother. As much as I get my energy from being around people, I also get recharged when I am alone. I read a lot. I am a lover of science. I am a lover of art. I am both/and. On some level I have always shirked what can be called typical forms of masculinity, the kind that only recognizes anger and limited happiness as acceptable forms of emotion, the kind that believes in only resolving disputes with fists, the kind that avoids displaying vulnerability. I found this rigid adherence to unspoken gender norms to be untenable for me. Now admittedly, I don’t quite fit the “I’m a lover, not a fighter” mold, but I try to be the same person with my friends who are men as I am with my friends who are women. I was (and have to remind myself that I still am) a poet and hopeless romantic, and those qualities make me vastly different from the example I had when I was growing up. Knowing this, I had to take stock of what fatherhood looked like for me when I became a father myself.

I am now the proud father of a nearly six-year-old daughter named Samara and a nearly two-year-old son named Solomon. Because my father and I are inherently “wired differently,” I had to both decide and design how this difference would look in my fathering form. The situation called for me to iterate on my experience with my father in order to create my own version of fatherhood.

During my first four years as the father to Samara, I was focused on making sure she received the affection she needed from me, as well as the support, humor, love, patience. I strived to model the character she needed to witness. It is also important for me to model—through my interactions with her mother—the way in which a healthy relationship looks. I remember holding her after she was born with tears in my eyes feeling incredibly grateful that God chose me to be her father. I took (and still take) that charge seriously, as

I try to embody healthy forms of masculinity she should both seek and demand from those around her as she grows up into the woman she is destined to be.

That means being brave enough to be vulnerable, to listen, to exercise what I call the three ‘selfs’: self-control, self-awareness, and self-efficacy.

When Solomon was born, I found that many persons expected that I would treat him altogether differently. I kept hearing statements like: “You got your boy, now!”, “Your name lives on,” and “He’s going to be such a heartbreaker.” The language around how our relationship was described was altogether different and loaded with stereotypical tropes centered around cultural and gendered heteronormative behavior. The expectation seemed to be that there would be a complete 180° difference in how I would raise Solomon and I would Samara. I remember saying at the time (and still maintain) that I want similar things for both of my children and that I don’t see many significant differences in how I would approach raising them.

As an Organization Development Practitioner and coach, I have studied a great deal of behavioral science including cognitive behavioral therapy, theories of intelligence, neuroplasticity, emotional intelligence, humanistic theory, and Appreciative Inquiry. They help inform my awareness in child-rearing.

When I consider who I would like my children to be my answer is that I want them to become courageous, passionate, loving, talented, brilliant men and women who have a deep and abiding faith; that their sense of family and agency are resilient; and that they have a healthy relationship with fear and failure.

Writer Olu Burrell and his daughter.

I say the latter because fear is a constant in the lives of every human being on the planet, but it manifests itself in different ways and degrees of intensity. The fear of failure can present itself as self-doubt and keep one from achieving their dreams, but understanding that failure is a necessary part of growth and achievement; we can better orient ourselves to the opportunity there is to be found in failing. It is a lesson I learn and relearn daily. It wasn’t always this way, however. It took me time to embrace the fact that I am not a human being, but a human becoming. It took me learning about the difference between a fixed and a growth mindset to understand the power of the language we use, and how small modifications can make a world of difference in how we see and engage with the world. I am learning daily how to embrace the opportunity that fear presents. I also realize that those outcomes, while not impossible, require a lot from me as their father.

It requires me to embody those things first.

How do I become a great father? By understanding that I still have much to learn, especially from my children.

Pablo Picasso once said, “Every child is an artist. The problem is how to remain an artist once you grow up.” Children’s natural curiosity, boldness, willingness to take risks and the like are emboldened when they feel supported and when they see mistakes and failure as opportunities to grow and change as opposed to blemishes to be ashamed of. I fight to be the artist I was as a child and will fight to ensure that they never lose the artists they are.

I think back to my father’s constant refrain of him “being wired differently.” I think I’ve always seen the truth in that statement, but it took for me to become an adult to see the wisdom of it as well. The simple act of acknowledging this statement is an ownership of one’s agency; it’s being unapologetic about what makes you unique, and different, and special. It’s a declaration I hope my own children find pride in, should anyone question why they don’t go along with the crowd.

It’s a testament to the enduring power of words passed from a father to his child; the kind of power I now wield.

When I answer the question of how do I become a good father, I must begin with the end in mind: what kind of human beings do I want to turn loose upon the world?

Those who are wired differently.

Related Articles

Bozoma Saint John talks Black motherhood, grief, self-love, and finding joy again. Don’t miss her powerful conversation on building legacy and living boldly.

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Black fathers Terrell and Jarius Joseph redefines modern fatherhood through love, resilience, unapologetic visibility in this Father Noir highlight.

Featured Articles

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

The vision for our engagement shoot was to celebrate ourselves as a Young Power Couple with an upcoming wedding, celebrating our five year anniversary - glammed up and taking over New York.

Meagan Good and DeVon Franklin’s new relationships are a testament to healing, growth, and the belief that love can find you again when you least expect it.

Our intent is to share love so that people can see, like love really conquers everything. Topics like marriage and finance, Black relationships and parenting.

HEY CHI-TOWN, who’s hungry?! In honor of #BlackBusinessMonth, we teamed up with @eatokratheapp, a Black-owned app designed to connect you with some of the best #BlackOwnedRestaurants in YOUR city – and this week, we’re highlighting some of Chicago’s best!