Paris is Burning and Pose

From the very beginning, media has had the ability to either smother fires and help us heal with one another or throw gasoline on those fires and scorch the earth.

There’s no doubt that media has evolved from what it once was, and I, as a proud child of the ‘90s, recognize that I benefited so much from that evolution. Before social media and Google, before YouTube and Netflix, we satisfied our primal need to experience stories with books and an ever-growing television and film industry. They painted pictures for us. Built our understanding of the world outside of our living rooms, and sometimes outside of our country. They managed to paint pictures so real that sometimes we forgot they weren’t. From the beginning, film has been an undeniable tool used to shape the way we see the world and the people around us. I use the word “tool” intentionally because from the very beginning media has had the ability to either smother fires and help us heal with one another or throw gasoline on those fires and scorch the earth.

From the very beginning, media has had the ability to either smother fires and help us heal with one another, or throw gasoline on those fires and scorch the Earth.

Actors wearing full regalia of the Ku Klux Klan chase down a white actor in blackface in Birth of a Nation. (Credit: cineaste.com)

In 1915, D.W. Griffith capitalized on the growing popularity of film with Birth of a Nation, a film adaptation of a novel by Thomas Dixon that would later go on to gain the worst kind of popularity as a weapon used to fuel racism in the Early 20th Century. Griffith constructed an incredibly ignorant portrayal of the period following the Civil War and entering Reconstruction that painted Black people as lazy, animalistic, and dangerous. It capitalized on the ignorance of white people and filled gaps in their knowledge of who Black people were, or could be, with propaganda that stripped us of any, and all, humanity we had left after enslavement. Who was the protagonist of the film, you ask? The Ku Klux Klan (I wish you could see my faces as I’m writing about this mess). It told such a compelling story, that as the film swept the nation it not only led to violence against Black people, but also laid the groundwork for the rise of the KKK. This was a clear indicator of how important media representation has always been and also a point of wondering for me. What if D.W. Griffith hadn’t been so damn ignorant? What if this film had been a step toward a major turning point in our country’s history with race? What if this film had told the story of who we are?

Toward the latter end of the 20th Century, I was unknowingly being brought up in a cultural high. Maxine Shaw showed me that I could be a lawyer, while Judge Phillip Banks showed me what it meant to remain true to your roots after you move on up to the deluxe apartment in the sky. At the same time, Phylicia Rashad gave me a dynamic portrayal of Black womanhood while Dwayne Wayne showed me that glow-ups were so attainable for me (and I needed it). I was witnessing a world where more of our stories were being told in more accurate ways than they had been in the past. We could be more than a sassy sidekick, or a one-dimensional character slapped into a script as a token. There were stories being told that elevated our complexity, our magic, but also our humanity. It demonstrated to people who might not ever come into contact with Black people, some small glimpse into our experience. It elevated our similarities and also elevated the ways in which we navigate oppression. It wasn’t always perfect, but it was progress.

Somewhere toward the end of undergrad, I embraced the rise of Netflix by thumbing through titles and landed on a documentary from the late ‘80s.

I could tell by the music in the opening scenes that this was going to be so ‘80s I could smell the curl activator.

I could tell by the music in the opening scenes that this was going to be so ‘80s I could smell the curl activator, but one of the first lines uttered set the tone for the film that would go on to impact the way I saw myself.

Related: The Art of Belonging: The Intersection of Race and Sexuality

“I remember my dad used to say you have three strikes against you in this world. Every Black man has two, that they’re Black and they’re a male. But you’re Black, you’re a male, and you’re gay. You’re gonna have a hard fu$%^#@ time. And he said, if you’re gonna do this, you have to be stronger than you ever imagined.”

Paris is Burning. (Credit: dazeddigital.com

Not without its own controversy and pitfalls, from that moment on, Paris is Burning became so much more to me than a documentary, it actually taught me pieces of history that I was either too afraid or too unwilling to go and learn about a community I was undeniably a part of. What television and movies taught me up to that point about my sexuality was that I could be three things: Your wise-crackin’ hairdresser, your wise-crackin’ sidekick, or your “sexually confused” boyfriend/husband. Either way, if the character wasn’t acting out some stereotype, they were either inflicting pain or experiencing pain as a result of their sexuality.

Up to this point, the only time I’d seen a loving queer couple, or a Black queer character leading a show, was that one year we could afford the good cable and I learned what Noah’s Arc was. I’d seen Will and Grace, watched every episode of Golden Girls at least three times, and even gotten into Queer as Folk at one point, but each of them in some way told a story that I could never see my Blackness in.

As I watched Paris is Burning, I gained more depth and clarity on the history of Queer People of Color (QPOC) than I ever got when those stories were told by others, and it was all too familiar to me. Each of them spoke of a world they created for themselves. When their families kicked them out, when the world and even members of their own racial community denied them any right to life or love, they provided for each other. When they faced insurmountable obstacles, they built families amongst themselves. And when no one else would celebrate their unique individuality and incredible humanity, they did what marginalized people have done for generations in the face of oppression. They built their own world.

When no one else would celebrate their unique individuality and incredible humanity, they did what marginalized people have done for generations in the face of oppression. They built their own world.

Jared Williams

For the first time, I saw myself in the most incredibly raw and unscripted way. I found myself envious of the way they embraced themselves and even managed to lift off so much of the weight that comes with non-heterosexuality. That, if only for the night of a ball, they were able to live beyond violent expectations that too often sounded like “You’re an embarrassment to your race” or “Quit acting like a faggot”. If only for the night of a ball, they embodied some liberation. So, I went out, and I got a lil liberated.

Some years later, after I had my own “coming out” and understood living my truth a little better, Steven Canals said, “Hold my got’damn beer” and brought me Pose on FX.

After Paris is Burning, I went on a sharing spree. Any friend of mine that wanted to keep me in their life and understand who I was finally allowing myself to become, was treated to a screening of the late-80s documentary with me. I wanted them to see where modern pop culture was taking, even stealing, from the lexicon that gave us “shade” and “reading” and so many of the other fun “quips” I hear ruined by people who often times don’t acknowledge us. I wanted them to see stories of QPOC that weren’t mired in tragedy. I wanted them to see queer people experience joy and acceptance in a way we’re rarely shown. I wanted to share something with them that made me feel privileged to call myself a queer, Black man. Even after all of this, never did I expect Steven Canals’ Pose to take my experience to the heights that it did.

When I talk about stories that move us closer to ourselves and closer to one another, Pose is definitely included in that list. From the opening scenes of the very first episode, I was comically introduced to characters that brought me back to the grainy film and authenticity I saw in the stars of Paris is Burning. What stood out to me the most, was the way that Pose told fuller, more intentional stories about the impact of HIV/AIDS on queer communities. Many of the narratives I’d seen growing up inspired fear and paranoia, stripping those living with AIDS, and even HIV, of any humanity, reducing them to nothing more than cautionary tales.

Pose. Credit: thetakeout.com

Steve Canals, and even Janet Mock, who directed the sixth episode of the series, told a story I had never seen or experienced from this perspective. They brought a humanity to that story in a way that only those who truly saw themselves in the characters they wrote about, could do. They constructed a deeper portrayal of the love and resilience that exists, and has always existed, amongst QPOC. They illustrated heartbreak, hope, faith, and even ambition in a way that exposed the connections that exist between us all. They manifested something incredible.

They illustrated heartbreak, hope, faith, and even ambition in a way that exposed the connections that exist between us all.

In a time where Pride Month is becoming more engulfed in corporate pandering, and where we’re all seeing the protections we once thought were unshakable be threatened by modern politics, I need stories that remind me of who I am. In the face of members of my own Black community who feed me the same oppression fed to them, I need stories that remind me of the lineage that comes with being a QPOC. In a moment where we see the youngest and most vulnerable of our society – queer children like Nigel Shelby and countless transgender people of color like Johana Leon or Muhlaysia Booker — losing their lives with little or no reaction from our community at large, I’m reminded that we aren’t done. As Black people, we aren’t done elevating our stories and our humanity to the white world, but as QPOC we are even further in our fight to justify our humanity within our own communities.

I can’t help but appreciate the queer actors, producers, and directors of color who are committed to telling our stories until they’re heard.

I can’t help but appreciate the queer actors, producers, and directors of color who are committed to telling our stories until they’re heard. I also can’t help but be reminded by their commitment and by the commitment of QPOC working to serve our communities that the world we all envision, the utopia of Black excellence that is constantly uplifted in the Black community also includes us. It includes queer love and queer families and queer success just as much as is does straight love, families, and success. My work? I will do my best to commit to having open and honest conversations to move people along who are willing to be moved. Should you decide that you aren’t willing, you arguing with yourself, sis.

Check out Paris is Burning on Netflix and Pose on Tuesday nights at 10 p.m. on FX.

Related Articles

Bozoma Saint John talks Black motherhood, grief, self-love, and finding joy again. Don’t miss her powerful conversation on building legacy and living boldly.

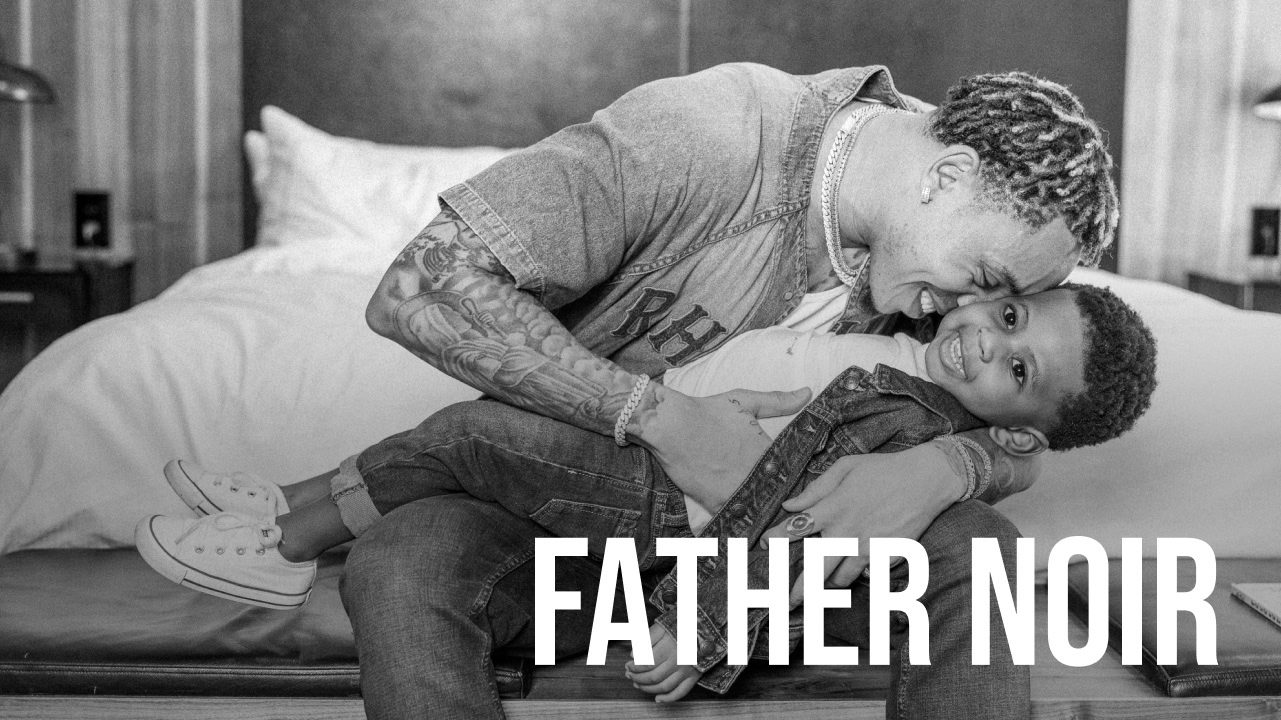

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Black fathers Terrell and Jarius Joseph redefines modern fatherhood through love, resilience, unapologetic visibility in this Father Noir highlight.

Featured Articles

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

The vision for our engagement shoot was to celebrate ourselves as a Young Power Couple with an upcoming wedding, celebrating our five year anniversary - glammed up and taking over New York.

Meagan Good and DeVon Franklin’s new relationships are a testament to healing, growth, and the belief that love can find you again when you least expect it.

Our intent is to share love so that people can see, like love really conquers everything. Topics like marriage and finance, Black relationships and parenting.

HEY CHI-TOWN, who’s hungry?! In honor of #BlackBusinessMonth, we teamed up with @eatokratheapp, a Black-owned app designed to connect you with some of the best #BlackOwnedRestaurants in YOUR city – and this week, we’re highlighting some of Chicago’s best!