Nipsey Hussle

Courtesy of Shutterstock

Courtesy of Shutterstock

There’s a hashtag relating to the late Nipsey Hussle that is as haunting as it is hopeful: #TMC. One year ago today, Nipsey Hussle “Tha Great” was gunned down in front of his store, The Marathon Clothing, located on West Slauson Ave. in Los Angeles, CA. The facility is the symbol of “Neighborhood” Nip’s evolution from gang member to activist and serves as an embodiment of second chances and community reinvestment. His death didn’t just leave us with a catalog of good music, but a record of great works with the mantra: “The Marathon Continues.”

That phrase, like Nip’s posthumous career, has enjoyed great commercial success. We as a community have interpreted the saying in different ways, whether as a statement of life and legacy, a standard for economic empowerment, or a denouncement of gun and gang violence. We are far from insensitive to the effects of poverty, crime, and systemic oppression in our own communities. That is why we gravitated to Hussle so strongly and mourned his passing. We identified with his ability to overcome personal adversity. But just when he was in a position to enjoy his success, it was quickly snatched away from him.

He aspired to reverse gentrification by bringing Black-owned businesses and jobs back to South Los Angeles.

Courtesy of Shutterstock

The ideal of #TMC is beautiful. It encapsulates our struggle and our progress as Black people. Sometimes, our self-analysis leads to pessimism. We criticize “Black on Black crime” or question financial management. However, Nipsey’s mantra isn’t just noble, it’s also benevolent, and a key component of teaching and reaching others is compassion. As we seek to understand this mantra, we should first understand Nip’s personal marathon.

The “paper chase” didn’t define Nip, and it shouldn’t define us either. What endears him to us isn’t solely based on economics; it’s empathy and artistry. “A solution built by an artist serves the artist more than the solution the capitalist comes up with,” Nip told Forbes in 2015. More than a decade prior, Hussle’s father, Dawit Asghedom, took Nipsey and his brother Samuel on a trip to their father’s native country Eritrea in East Africa. Back in 2004, he said the trip inspired him to become an activist with an “entrepreneurial spirit.”

When Nip dropped The Marathon mixtape in 2010, his goal was a return to independent sales. He successfully left Epic Records and released the album on his very own label, All Money In. That “declaration of independence” led to a follow-up album, “The Marathon Continues.” His self-determination and business savvy paid off in 2013 when Jay-Z famously bought 100 copies of his Crenshaw mixtape, as part of a $100,000 haul for Hussle.

Related: 3 Nipsey Hussle Inspired Ways to Invest in Your Community

His transition from independent artist to community investor can be described in his words through an excerpt from “Blue Laces 2,” one of the songs on his Victory Lap album:

Dropped out of school, I’m a teach myself

Made my first mil’ on my own, I don’t need your help

All black Tom Ford, it’s a special evenin’

City council meetin’, they got Hussle speakin’

Billion-dollar project ’bout to crack the cement

So one of our investments had become strategic

Summer roll ’18, man it’s such a season

‘Bout to make more partners look like f—in’ genius

We was in the Regal; it was me and Steven

We done took a dream and turned it to a zenith

Nipsey Hussle’s vision equated to independence, the importance of investing, and an interest in local politics, which prompted the transformation of his community. He aspired to reverse gentrification by bringing Black-owned businesses and jobs back to South Los Angeles. He gave back to young people through educational initiatives, giveaways, and renovation projects. Again, he wasn’t defined by his money.

He spoke openly about gang life as a means of outreach for younger generations. The day before his murder, Nipsey was scheduled to speak with the Los Angeles Police Department about gun violence in the local community. That fact only made his death even more of a cruel twist of fate.

The ideal of #TMC is beautiful. It encapsulates our struggle and our progress as Black people.

Credit: TheCurrent.org

In February of 2018, I became a fan of Nip shortly after the release of his only studio album, Victory Lap. The song that caught my attention was “Double Up.” It’s the type of ubiquitous record that you can play whether you’re in a happy or somber mood, chilling at home, or riding late at night. I lamented at the fact that I’d learned about his greatness so late in the game but he had a fan in me from the time I heard that first single. When the video dropped for “Double Up,” there was no doubt that Nip would make the transition from mixtapes to commercial success. And then, just like that, he was gone.

Double up

Three or four times, I ain’t tellin no lies, I just run it up

Never let a hard time humble us

Do-do-double up

I ain’t tellin’ no lies, I just (yeah)

I ain’t tellin’ no lies, I just

Five, four, three two

That’s time, I got, to you

That money, my dreams, come true

My life, in diamonds, who knew?

Who knew? Who knew?

My point exactly. Who knew Nipsey’s death would resonate with so many people? Who knew that in death, he would attain the level of stardom and sainthood associated with the likes of Tupac Shakur?

Nipsey Hussle “Tha Great” answered those questions through his actions, the way he lived, the legacy he created and, the symbol of hope he has instilled in many of us individually and within our local communities.

Related Articles

Bozoma Saint John talks Black motherhood, grief, self-love, and finding joy again. Don’t miss her powerful conversation on building legacy and living boldly.

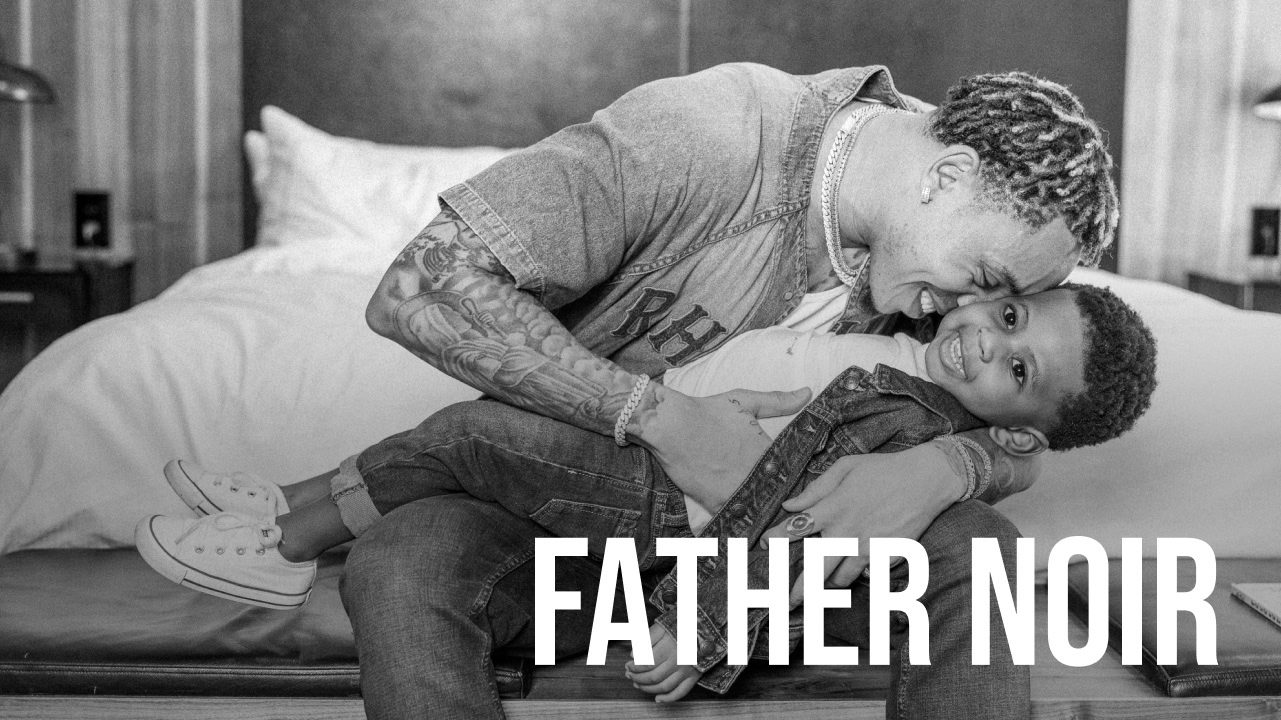

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Black fathers Terrell and Jarius Joseph redefines modern fatherhood through love, resilience, unapologetic visibility in this Father Noir highlight.

Featured Articles

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

The vision for our engagement shoot was to celebrate ourselves as a Young Power Couple with an upcoming wedding, celebrating our five year anniversary - glammed up and taking over New York.

Meagan Good and DeVon Franklin’s new relationships are a testament to healing, growth, and the belief that love can find you again when you least expect it.

Our intent is to share love so that people can see, like love really conquers everything. Topics like marriage and finance, Black relationships and parenting.

HEY CHI-TOWN, who’s hungry?! In honor of #BlackBusinessMonth, we teamed up with @eatokratheapp, a Black-owned app designed to connect you with some of the best #BlackOwnedRestaurants in YOUR city – and this week, we’re highlighting some of Chicago’s best!