Courtesy of @ editaurial/Instagram

Courtesy of @ editaurial/Instagram

There are some summer days when I wake up with the sun, lather on my shimmering 40 proof sunscreen, throw on two mix matched bathing suit pieces, and catch the first train to Rockaway Beach. When I arrive, I stretch my towel and my legs out in the sand. I say hello to the seagulls circling the sky, inhale my first big, deep breath, and release any tension I’ve carried over from the day before. I open my heart chakra, press play on my favorite playlist, then proceed to shake my ass for at least 45 minutes. This is my meditation. Bouncing across the beach I swing my hips with the motion of the waves, crashing into conga drums and the sweet rhythms of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora. I pop, lock and drop it onto the shore, smiling with all 32 of my teeth, spinning and twirling and twerking. I get lost in the symphonies of lost people who found their way through music. The sounds of a land I’ve never known but have felt it’s soil through soca. Felt it’s joy in a djembe.

I was born in Buffalo to an Irish mother and a father whose lineage cannot be traced. I also was born a Black girl, a biracial girl, a descendant of slaves. I grew up in low-income neighborhoods with kids who looked like me, talked like me, danced like me. We listened to the same music, and none of my peers batted an eye when someone began popping it or, as the young folk say these days, throwing that thang! In fact, we sometimes had twerk contests at our neighborhood block parties where young women would line up and showcase their skills. This was the early 2000s so you got bonus points for getting as close to the ground as possible. The Ying Yang Twins’ “Say I Yi Yi” would blast from somebody’s stereo and I’d stare mesmerized as beautiful women began to match the beat with their bodies. They wore gold jewelry and dresses that accentuated the movement of their hips. The fabric flowed freely as their levels changed. With their hands on their knees, elbows on their thighs, they bounced around the concrete like they were the instrument. I watched but couldn’t join because little girls caught poppin’ it were labeled fast, and provided a first-class flight to the whoopin’ of their life. So, instead, I’d practice with my cousins, locked away in my bedroom, dreaming of the day when I was grown enough to get down.

View this post on Instagram

That day came my freshman year of high school at a house party with one of my closest friends who hadn’t grown up the way I had. There were no block parties in her childhood, only Sunday services, and girl scout camps. As we walked around, I watched as sweaty teenagers bounced against each other under blacklight. Pretty Ricky’s “Grind On Me” echoed throughout the basement, and I couldn’t wait to unleash the body roll I’d been practicing on my door frame. I felt my hips begin to loosen, and right before they dipped into position, my friend leaned over and shouted above the music.

“Look at how these girls are dancing. So ghetto!”

“Yeah,” I mumbled back “so ghetto,” then stood up as straight as a nail.

In the dark corners of that basement, I cloaked myself in courteousness.

Fearing judgment, I stiffened my spine and became what I believed to be a respectable Black girl.

Respectable Black girls didn’t take up space. Respectable Black girls didn’t flaunt their curves. Respectable Black girls didn’t twerk. Respectable Black girls were palatable, confined. We chose to shrink rather than run the risk of offending others with our existence. Respectable Black girls diverted attention. We say don’t look at me, look over there! Look at yourself. Let me help you see yourself through erasing all of me. Take my hips. I don’t need them. Take my lips. Take my style. Take my rhythm. I will give them to you in exchange for acceptance. In exchange for safety. In exchange for you to release the pressure of your foot on my neck, I bathed in this identity. Pretending to be disconnected from the culture that marinated me.

At future parties, I stood against the wall, or worse I’d intentionally dance offbeat. “Tauri is such an Oreo” my peers joked as I flared my arms in the air like one of those blow-up creatures that flap outside of car dealerships. I smiled at their approval. I sunk deeper into the cloak, embarrassed of what my body revealed about me to others. That embarrassment would follow me all throughout high school, and well into college. Eventually, it would turn into doubt that I would use to question the value of my being. Before long, I hadn’t a grasp on who I was beyond the expectations of others, but one thing remained consistent. Though I denied it with every fiber in my being, the sounds of steel drums and an upbeat tempo sent me into a euphoria I couldn’t explain.

Then, I took my first Black Studies class. I was introduced to the concept of diaspora or the dispersion of people from their original homeland. One day, as I sat through a lecture on the evolution of Black cuisine -from Africa, through the slave trade, and all the way up to modern-day- an epiphany crept up and slapped me right on the forehead. Of course, my body desired to surrender to the sweet sounds of South African house music. Its percussive beats date back to a time before I was born. A time when I was the biggest dream my ancestors could imagine as they prayed for me in drum circles, in jazz clubs, in hymns sung on cotton fields. Through music and dance my ancestors carried their culture across oceans. Held on to what they could, recreated what they were forced to let go of. An endless evolution of storytelling. Of joy and innovation. Of freedom in the form of self-expression. To deny myself of these liberties was to deny the diaspora and my connection to a legacy much larger than my individualized experience.

After coming across this realization, I was so excited I could twerk right there in my seat. So, I did. Then I twerked outside of the classroom. Twerked at the bus stop and on the bus ride home. I twerked in the dining halls. At house parties. At homecoming. And right before I walked across the stage at graduation. I twerked so much when people met me for the first time they’d introduce themselves by saying “I think I saw you dancing somewhere,” and the chances were they probably did. Dance connected me to my ancestors and produced the kind of happiness I refused to contain in order to contribute to a colonized culture that didn’t include me. If that makes me ghetto, then so be it.

View this post on Instagram

Every day, Black women are asked to shrink. To make themselves less visible, less tempting, less aware. We are provided with conditions in which we can exist, roles to play that don’t offend: caretaker, sidekick. We are asked to hide ourselves, our bodies, our desires. All in the name of respect. And while I acknowledge this respect often correlates with our safety, I must also point out that we exchange our joy, pleasures, and freedom for this safety. We don’t dance the way we want. Don’t dress the way we want. Don’t speak in a language that feels familiar. We become shadows of ourselves, walking beside our bodies rather than within them.

Sometimes when I am dancing, other women will approach me and ask where my confidence comes from. What they really want to ask is how did I build up the courage to take up space publicly. To be unapologetically Black and woman without fear of judgment, labels, and retaliation. I tell them that dance brings me joy, and in a world that goes out of its way to steal my smile, joy is always worth resistance.

Related Articles

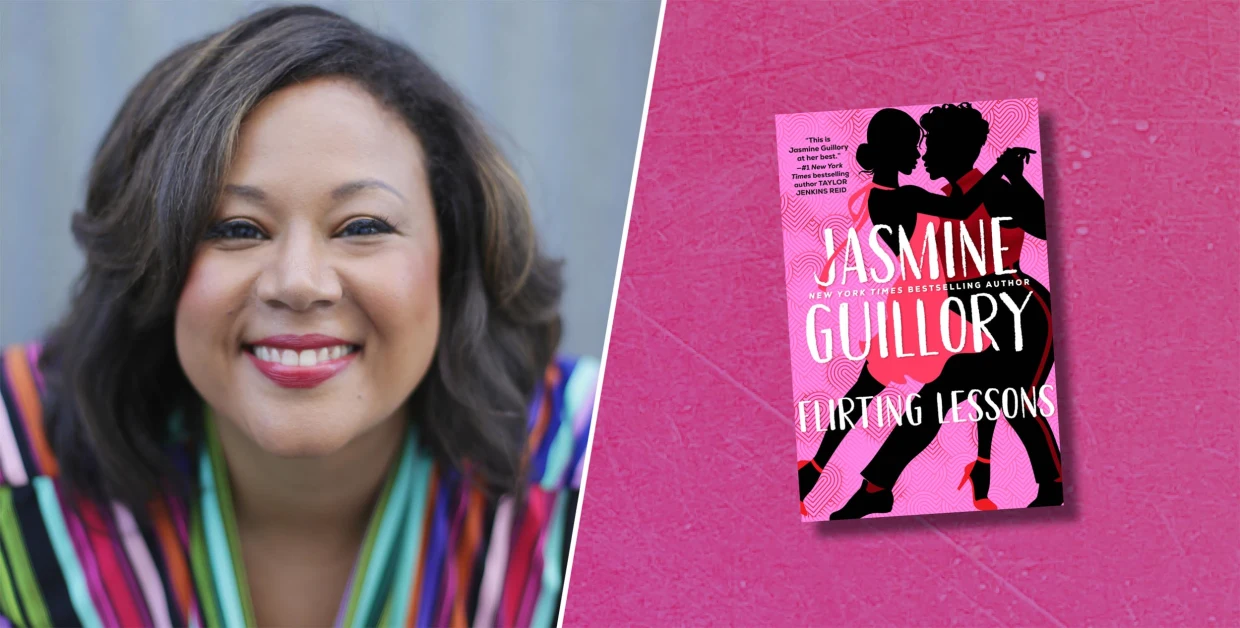

Discover why Jasmine Guillory’s latest novel Flirting Lessons is a must-read—and how the author continues to redefine modern romance with layered Black heroines, real emotional depth, and Black literature that feel both magical and true.

Bozoma Saint John talks Black motherhood, grief, self-love, and finding joy again. Don’t miss her powerful conversation on building legacy and living boldly.

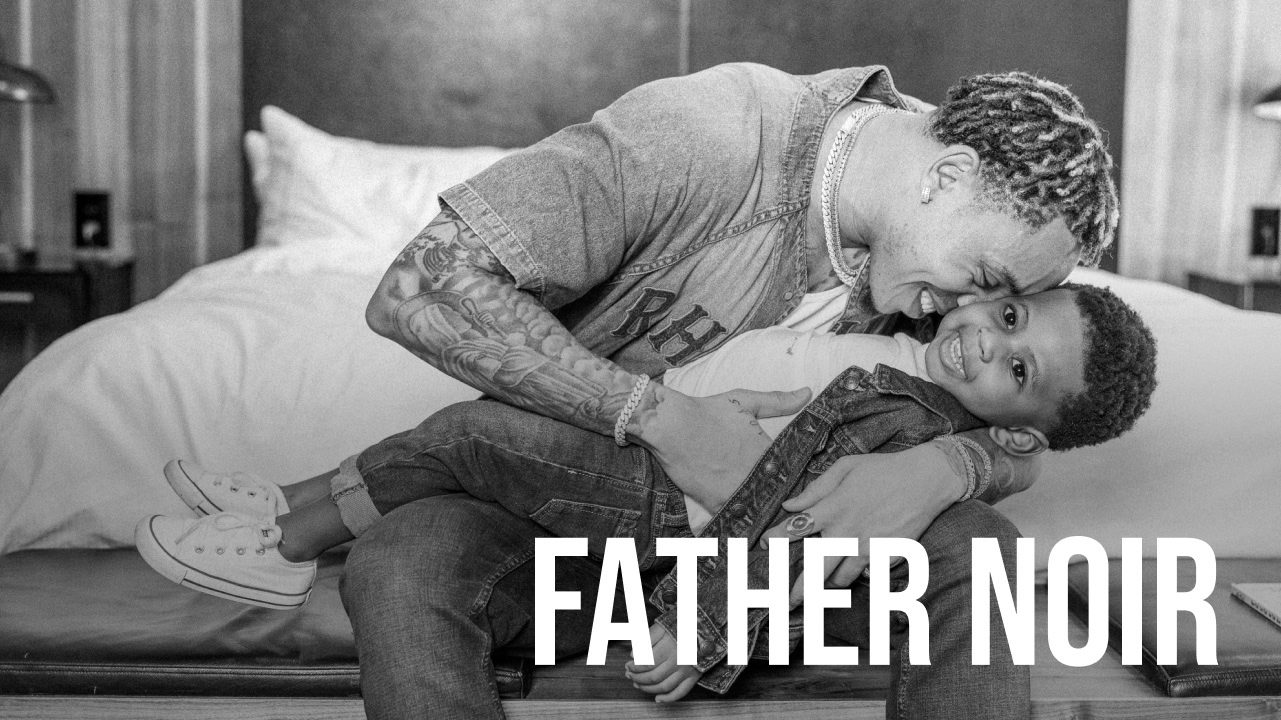

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Featured Articles

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

Our intent is to share love so that people can see, like love really conquers everything. Topics like marriage and finance, Black relationships and parenting.

The vision for our engagement shoot was to celebrate ourselves as a Young Power Couple with an upcoming wedding, celebrating our five year anniversary - glammed up and taking over New York.

HEY CHI-TOWN, who’s hungry?! In honor of #BlackBusinessMonth, we teamed up with @eatokratheapp, a Black-owned app designed to connect you with some of the best #BlackOwnedRestaurants in YOUR city – and this week, we’re highlighting some of Chicago’s best!

Meagan Good and DeVon Franklin’s new relationships are a testament to healing, growth, and the belief that love can find you again when you least expect it.