Screenshot

It had been on my radar, mainly because of the powerhouse duo of Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan, who directed and starred in the film, respectively. From Fruitvale Station to Creed and Black Panther, these two continue to redefine excellence in modern Black entertainment. Their partnership is a testament to what can happen when Black filmmakers support one another in an industry that often sidelines us. As Black movie directors and producers, Coogler and Jordan are setting a new standard for Black representation in media, one that is authentic, layered, and community driven. Their work reflects a healthy brotherhood, deep friendship, and powerful business partnership that models successful unity within the world of Black artists and creatives. In an industry that has historically marginalized Black entertainers and creatives behind the camera and on camera, their ongoing success feels revolutionary. Together, they are breaking barriers and reimagining what’s possible for Black representation in Hollywood and beyond, as seen in Sinners.

What immediately stood out to me about Sinners was that it was an original IP completely free from an existing franchise or cinematic universe. It was something bold, fresh, and new. All I knew going in was that it was Coogler, Jordan and a strong supporting cast, and that it had something to do with vampires. What drew me in even more was how Coogler engaged with audiences during the press tour whether through breaking down visual language, discussing the technical craft, and being transparent about the creative process. He wasn’t just promoting a film; he was inviting us into the art of filmmaking itself. That kind of honesty and intentionality builds trust and makes you want to lean in even closer.

Still, I was late to the party and that’s important to note, because Sinners gave me something I haven’t felt in a while: a real sense of FOMO. What started as a casual “I’ll check it out eventually” turned into “What is everyone talking about, and what am I missing?” I couldn’t escape the buzz. In barbershops, classrooms, stores, social media, and anywhere else I went, someone was asking, “Have you seen Sinners yet?” What finally pushed me to go see it was witnessing people I know, people who hate horror, willingly going to see this film. Friends who’ve avoided anything remotely scary for years were making exceptions. I’m talking about people who still to this day avoid watching Courage the Cowardly Dog or even Michael Jackson’s Thriller music video, but all of a sudden are ready to pull up to Sinners. That made me pause and ask: What is it about this film that’s pulling people beyond their limits?

It became clear that this was more than just a movie. This was a cultural moment. A collective experience. The film’s success is undeniable. It was dominating the box office, lighting up the timeline, and inspiring repeat viewings with some going back two, three, even four times. The hype wasn’t fading; it was building. So, I went.

And when I walked out of that theater…

I was speechless.

From the moment the credits rolled, I understood the hype. Sinners felt completely new, yet strangely familiar. Every detail felt intentional. The storytelling was layered, poetic, and rich with purpose. My mind couldn’t stop racing. What struck me instantly was how differently it landed for everyone I talked to. My interpretation didn’t align with my friends’, and as I kept talking to others, I realized: Sinners is an even more deeply layered film than I initially assumed. Everyone walks away with something unique. That’s why people keep returning. Each viewing uncovers new meaning, new symbols, new truths.

It reminded me of replaying a favorite song. You catch something new every time like a lyric, a beat, an emotion that hits differently depending on where you are in life. Since watching it, I’ve been asking people what they took from it. And if they haven’t seen it, I urge them to go. Not just to watch, but to experience it. Because every voice, every perspective, adds to the larger conversation.

Sinners isn’t just a vampire film. It’s not just horror. Sure, it wears the visual language of horror, but it’s rooted in something far deeper. Historically, horror has always served as a reflection of the anxieties of its time. The best horror unsettles us not just because of monsters, but because it exposes truths we’d rather ignore. Sinners does this with a distinctly cultural and historical lens. It’s not only about fear. It’s about identity, memory, lineage, resistance.

Ryan Coogler didn’t just make a genre film. He made a cultural artifact. A love letter. A spiritual reckoning. A piece of living, breathing art that honors Blackness in all its complexity. You can feel it in every frame: religion, race, trauma, legacy, joy, love, and survival. It’s expansive but precise. Not monolithic, but richly interconnected.

Sinners opens the door to layered conversations deeply reflective of the Black experience. Some of the conversations I’ve had center around the tension between twin brothers Stack and Smoke’s romantic lives, with one navigating an interracial relationship with a Black woman who is White-passing, and the other embodying the complexities of Black love. These contrasts highlight relationship traumas, colorism, and the nuanced process of navigating biracial identity. At the same time, they underscore the healing potential and freedom found in healthy Black relationships and the value of honoring healthy boundaries in relationships.

Blues music plays a central role in the film, carrying the weight of history, grief, and ancestral power. The sounds of blues music echo throughout the narrative, serving as a connective thread between generations and as a tool of resistance. The contributions of Black musicians are portrayed not simply as entertainment, but as sacred expressions that channel cultural preservation, spiritual truth, and emotional release. Gospel music, gospel jazz music, and Southern soul music also subtly inform the film’s sonic atmosphere, paying homage to the deep-rooted influence of Black jazz musicians and the legacy of Black musical traditions.

The intimacy and vulnerability shared between Stack, Smoke, and their younger cousin, Preacher Boy, challenge the harmful stereotypes often imposed on Black men. Their brotherhood creates space for emotional complexity, tenderness, and healing which move beyond the stoicism that is so often expected.

Sinners doesn’t shy away from the heavier themes either. It confronts the broader systemic forces that continue to shape and suppress Black life from the suffocating grip of capitalism to the evolving face of exploitation and modern colonization, now disguised as opportunity, ownership, and access. The film reminds us that evil must be invited in. It doesn’t just appear and in doing so, it prompts reflection on the roles we each play in either perpetuating or resisting harm.

Sinners explores what it means to be loyal, to belong, to believe, to resist. It echoes the complexity of navigating Blackness in the 1930s, a period of survival and fear that still lingers today. The horror isn’t just supernatural, it’s systemic. It reminds us that even if we survive what haunts us at night, we still face the violence that exists in broad daylight. No amount of wealth, colorism, migration, or proximity to power or Whiteness can fully shield us. The monsters or temptations may change shape, but the dangers remain. And just because we’re alive doesn’t mean we’re truly living. What endures and what brings us life is our capacity to choose: to choose love, to choose life, to choose each other. To build family and community rooted in love in all its forms: self-love, communal love, familial love, romantic love, cultural love, and more. Even when society and the world feel unstable, these are the things that ground us. They remind us that while we may not always be protected, we are never powerless and we can still feel fully, deeply alive.

That’s why this film is hitting so hard and why even people who usually avoid horror are showing up. Because Sinners is more than a movie; it’s a gathering. A conversation. A mirror. A moment. The music, the setting, the wardrobe and everything in between, they don’t just support the story; they live in it. Like music, Sinners is timeless. It reaches across generations, across the diaspora. It’s a cautionary tale and a celebration all at once. It warns of what happens when we give others access to our world without boundaries. And it shows the beauty of protecting and preserving what’s sacred.

Related Articles

Explore Michelle Obama's raw honesty about adapting to life as empty nesters and its impact on Black love.

Explore how 'The Chi's' end brings insights into love and community growth. Discover lessons Black couples can embrace.

Explore Marlon West's story and learn how music shapes Black love, relationships, and growth.

Featured Articles

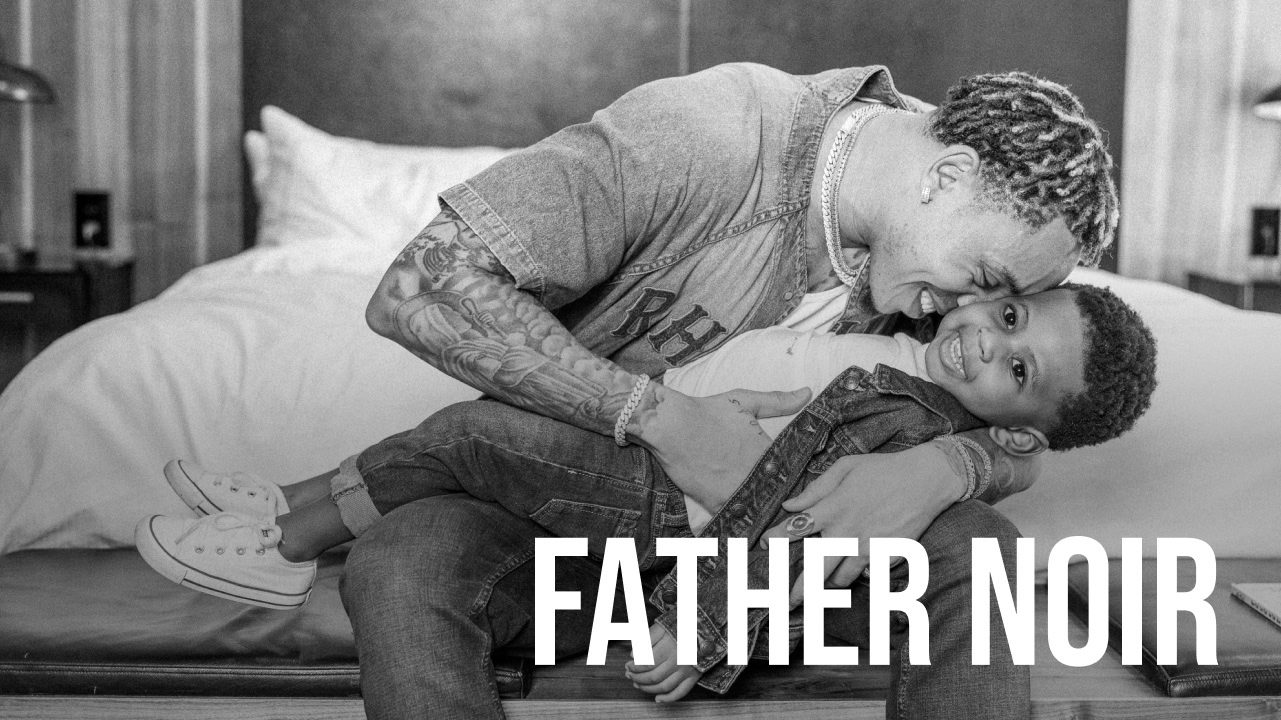

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

Black Love caught up with Justin and Patrice Brim to delve deeper into their journey, unpack their inspirations, and discover what lies ahead for the incredible duo.

Is the “mama’s boy” misunderstood? One writer breaks down how raising her sons has reshaped her thoughts on the complicated term.

The Smurfs are back July 18—and Couch Conversations for Two is celebrating with a heartwarming episode.

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.