Tauri Janee (Courtesy of @editaurial/Instagram)

Tauri Janee (Courtesy of @editaurial/Instagram)

Tauri Janee (Courtesy of @editaurial/Instagram)

My father used to send me letters from jail. His contributions to parenting scribbled out on torn pieces of yellow notebook paper. Most of his letters were brief, check-ins on my progress in school and reminders to stay focused. Others went on for pages, lectures on behaving for my mother and a persistent push for me to follow my dreams. My favorite included a drawing of two cartoon cats, their tails tangled together as they parted ways. I liked cats. l watched cartoons. I thought to myself, “my father loves me.”

The first letter came on March 17, 2002. I was 6 and couldn’t read so my mother sat me on her lap and we flipped through the pages together. “Daddy is not far away, just out of town for a few weeks. I’ll be back soon. Be good for Mommy. Stay smart and beautiful.” He signed at the bottom of the page in his best penmanship. “Is Daddy on vacation?” I asked as my mother stuffed the notebook paper back into its envelope. “He’s on a different kind of vacation” she responded, which I assumed meant he was on the best kind of vacation and began to imagine my father poolside with cucumbers on his eyelids.

By the time I was 10, I’d take the letters up to my bed and read them alone on my Hello Kitty comforter. As I traced each word with my fingertip, I’d attempt to visualize the room from which my father wrote. I imagined a brand new vacation home with matching furniture and a fuse-ball table. There were board games and a swimming pool and a dishwasher that worked. It was on the beach because I loved the beach, and though I didn’t know much about my father, I hoped we liked the same things. Sometimes his letters confirmed that we did. Like when he told me about a fishing trip he’d been on and I had my mother take me to a hardware store to pick out a new pole, determined to find a hobby over which we could bond. I read books about Salmon and Bluegills and Trout. Watched an obnoxious amount of Animal Planet. Collected worms from the yard for bait. “My daddy’s gonna take me fishing when he comes back from vacation,” I bragged to my classmates. Then, suddenly, the letters stopped.

If I cried, I don’t remember, but I do remember the disappointment. The sinking in my stomach as I sat by the mailbox waiting for what I was sure would never come. “I’m sorry” my mother sighed as I sank silently into her lap. For the first time since my father’s vacation, I truly felt abandoned.

I still went fishing, but not until 4 years later on a camping trip with my grandfather. I caught one fish and screamed at the horrific image of the slippery creature flopping about the boat with a hook jammed in his jaw. I never went fishing again, but I found other hobbies. I played softball. I ran track. I joined a cooking class. My life continued. I graduated high school, then college. I got my master’s degree. I moved to New York. I fell in love. Became a woman. Became a writer. As time went on, the image of my father’s vacation home faded away along with the image of my father himself.

Related Articles:

My Dad, Me, and the Healing Power of Forgiveness

How Do I Become the Father My Children Need?

Omarion on the Power of Fatherhood: ‘It’s a Part of My Purpose’

Courtesy of unsplash.com

Six months ago, if you asked me what I knew about my father, I’d tell you he was a Leo. That his name was once Humza then he changed it to Anthony, but everyone calls him Honzo. I’d tell you that he sold crack, but mostly went to jail for failed child support payments. I couldn’t tell you how many kids he has, but I could tell you that I’ve met at least 6, including one who reached out from Nova Scotia. I don’t know what my father was doing in Nova Scotia, but I know it wasn’t parenting because when my brother reached out he had so many questions about the man responsible for our birth, and all I could tell him was that I think he might like fishing.

My siblings and I dealt with our abandonment in uniquely different ways. Some chased after our father, longing for acceptance. Others, like my oldest sister, communicated with him in sporadic bursts of rage. She’d scream into voicemail messages and write long, detailed Facebook posts about his failures. She allowed herself to really feel the anger that often comes with being left behind. For this, I admired her. Me on the other hand, I dealt with my abandonment the way I deal with most uncomfortable things, by pretending it didn’t exist. I tucked his letters and all of my feelings in a converse shoebox, then buried it in my bedroom closet beside a precious moments bible. I’d given up on waiting for men who never came around.

I surrounded myself with women. I had women friends. I worked at a women’s co-working space. I signed up for writing workshops where the participants were women. In these spaces I talked about my experiences with men, but never my father. That is until I was provided a writing prompt that pushed me to respond to a letter and immediately the yellow notebook paper came to mind. I thought to myself, how does one write to a stranger? I started with what I knew. I introduced myself and told him about the woman I’d grown to be. On and on I went about my quirky life experiences. How I once climbed a 3,000 foot mountain. Once ripped my pants in a Berlin nightclub. Letter after letter, I outlined my life on the page. As the story grew, so did my curiosity about the man meant to receive it.

What was my father’s favorite color? I called my mother with a list of questions. Where did they meet? How did they fall in love? What did he usually eat for dinner? Curiosity consumed me. I googled public records. Searched for him on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter. I learned that his mother died of a drug overdose. His father, a rolling stone. He grew up with his grandparents who fed him pigs feet with red beans and rice until they, too, faced untimely deaths. I’m sure he had dreams, but I’m not sure what they were. For a moment where he took an interest in flipping houses, but soon realized that profit came quicker from people than properties. He quit school. He sold drugs. He learned to survive on his own. Inevitably, he made mistakes. Some of which cost him his family, many that cost him his freedom. With every bridge he tried to rebuild, the side effects of his poor choices eventually came crashing down upon it.

Courtesy of unsplash.com

As my father’s story unfolded before me, I realized it was not exclusively his own, but rather the story of many trapped in the cycle of poverty, mass incarceration, and other systemic injustices that oppress Black men. And although these are not excuses for his absence, they allowed me to detach myself from the narrative of a forgotten child. My father’s absence wasn’t personal. In fact, I don’t believe it was about me at all. Accepting this truth helped me empathize with him as a member of my community, placing him in the same category of those I march for at rallies. Despite the disappointment, my father is who I write poems for. He is Eric Gardner. He is Mike Brown. He is more than the worst results of racism. Through writing him letters, I found liberation in vulnerability, in freeing myself from justice defined by suffering or revenge. I like to imagine he felt this same freedom on the lines of that yellow notebook paper. Perhaps he wrote for the same reasons that I do now, to search for answers in an unfinished story.

Today, if you asked me to tell you about my father, I’d tell you that he was once a boy. One without a mother, without a father, without a home. I’d tell you about prisons and parole officers and how easy it is to get caught up in a system designed to destroy you. I’d tell you about the ’80s, Ronald Reagan and crack cocaine. I’d tell you about concentrated poverty rates in Buffalo, New York. I’d tell you about shot camps. I’d tell you about street culture. I’d tell you about violence that targets Black boyhood. More importantly than all of these things, I’d tell you that I forgive him. That forgiving him has helped me see him. Helped me humanize him. Helped me heal.

Related Articles

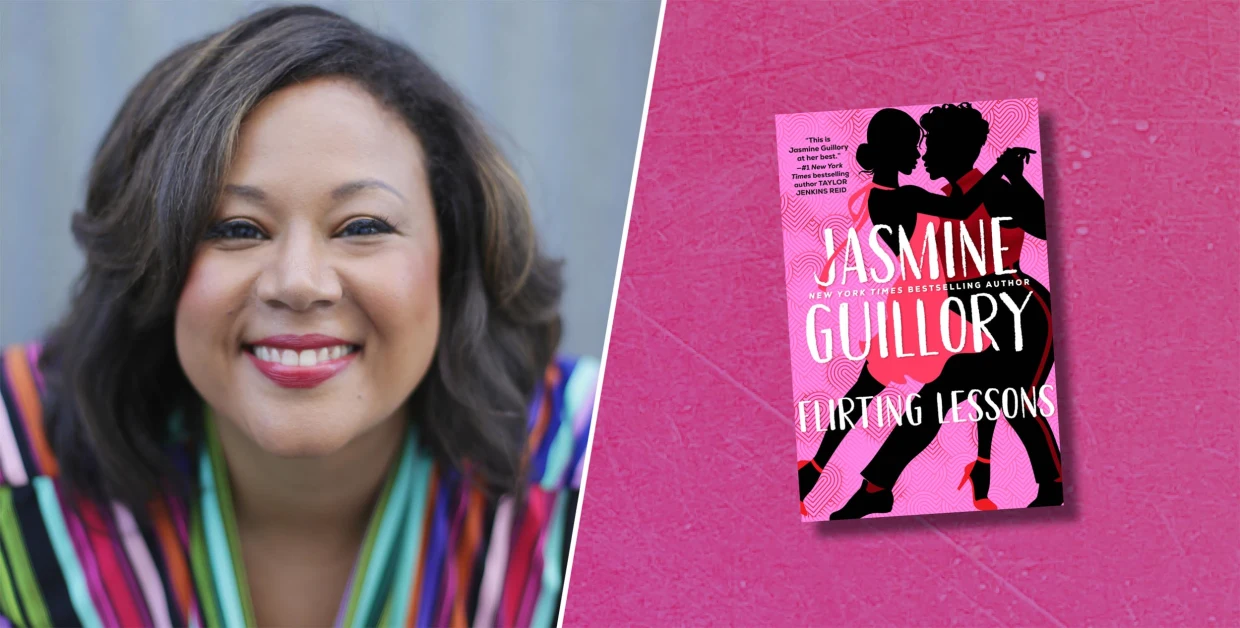

Discover why Jasmine Guillory’s latest novel Flirting Lessons is a must-read—and how the author continues to redefine modern romance with layered Black heroines, real emotional depth, and Black literature that feel both magical and true.

Bozoma Saint John talks Black motherhood, grief, self-love, and finding joy again. Don’t miss her powerful conversation on building legacy and living boldly.

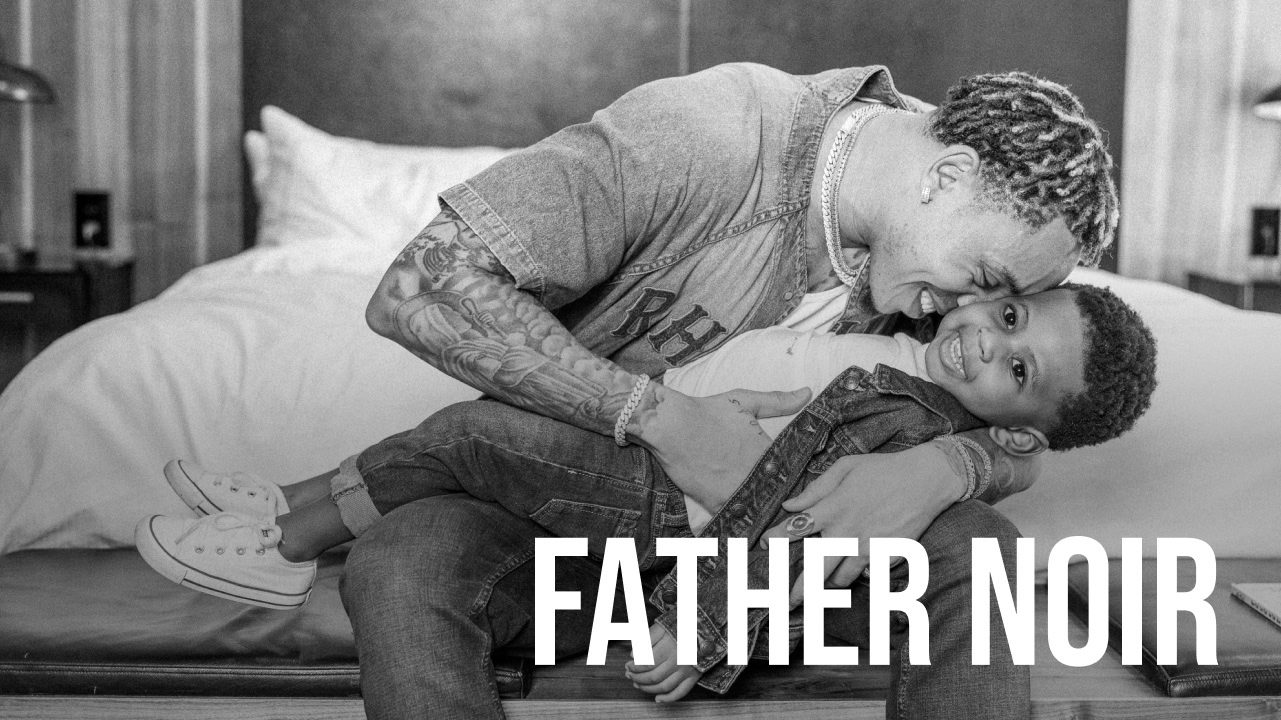

Tyler Lepley shows the beauty of Black fatherhood, blended family life with Miracle Watts, & raising his three children in this Father Noir spotlight.

Featured Articles

When Elitia and Cullen Mattox found each other, they decided that they wanted their new relationship together, their union, to be healthier and different.

Celebrate their marriage and partnership with the release of the documentary “Time II: Unfinished Business”

Our intent is to share love so that people can see, like love really conquers everything. Topics like marriage and finance, Black relationships and parenting.

HEY CHI-TOWN, who’s hungry?! In honor of #BlackBusinessMonth, we teamed up with @eatokratheapp, a Black-owned app designed to connect you with some of the best #BlackOwnedRestaurants in YOUR city – and this week, we’re highlighting some of Chicago’s best!

The vision for our engagement shoot was to celebrate ourselves as a Young Power Couple with an upcoming wedding, celebrating our five year anniversary - glammed up and taking over New York.

Meagan Good and DeVon Franklin’s new relationships are a testament to healing, growth, and the belief that love can find you again when you least expect it.